Evolution and Counter-evolution

The Covid virus, as it appears to us in drawings like this one, has a certain prominence in the global news. Of course our main interest is in the threat it poses to us humans. Some have seen positive aesthetic qualities, too — symmetry, proportion — although these are necessarily in the drawings. Yet another remarkable feature is the speed and variation with which it evolves, presenting new configurations, dividing, recombining, etc. every few months or even weeks. By contrast, we don’t evolve at all — or don’t seem to.

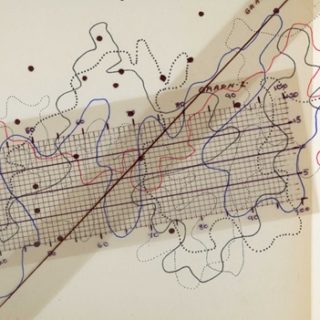

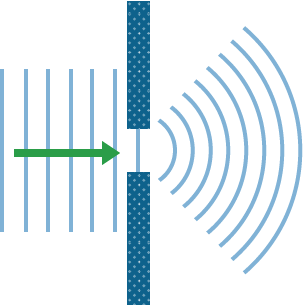

But there is a view of our evolution — and it isn’t even very new or speculative — that suggests that we have evolved just about as fast as the virus. Suppose technology is the way humans have evolved, that is, instead of adapting to change through the slow reshaping of a body, as most animals and plants do, we rely on our capacities to locate and shape materials for food and protection, on extensions of our perception — especially sight and hearing — to extend our memories and project possibilities? Without significant changes in our bodies, we’ve built a tremendous, thick envelope of objects and symbols around ourselves — effectively transformed our environment beyond recognition. From that standpoint, we have speedily evolved into beings with a range of defences against the virus, and continue to develop quickly in response to specific changes it presents.

Let’s say evolution is a process of turning indeterminate into determinate, inchoate stuff into objects or bodies, possibilities into specificities. It is effectively a process of creation. At some point human beings more or less took creation into their own hands, a tremendous advantage in some respects — and a terrible responsibility.